For decades, NASA has faced challenges concerning the management and sustainability of its numerous centers, largely due to Congressional resistance to consolidation efforts aimed at cutting costs. The agency encompasses a vast network of 38 rocket engine test stands located at six sites across the United States, each representing significant investments of public resources, with many now standing idle. As reported by the NASA inspector general, by 2026, only ten of these stands are expected to be operational, primarily because of the shift towards private spaceflight companies, notably SpaceX, which have taken over much of the rocket development workload. This reality reflects broader systemic issues within NASA, characterized by an overabundance of aging infrastructure that Congress traditionally preserves to protect jobs in their respective districts.

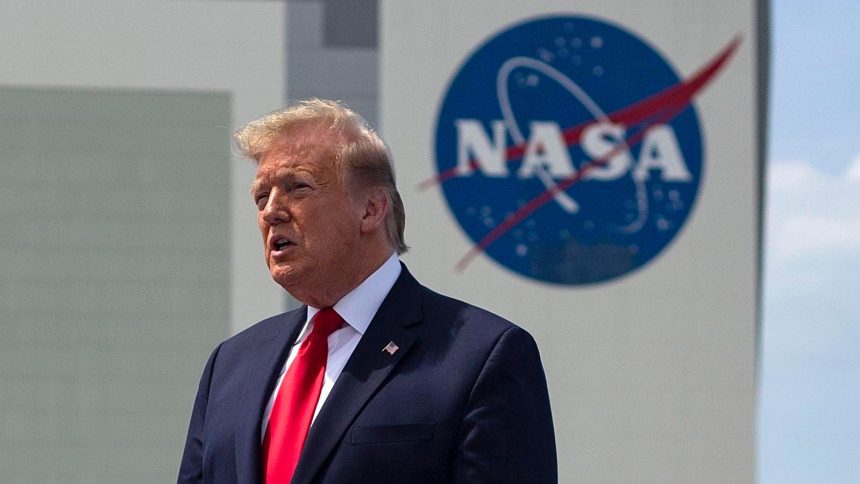

As the political landscape shifts with the return of Donald Trump to the White House, the prospect of aggressive cuts and reforms within NASA’s structure looms large. Trump’s administration, aligned with influential figures like Elon Musk, appears poised to tackle the politically daunting task of reducing the number of NASA’s major operational centers. While there is widespread consensus among some Republican policy insiders that NASA’s ten centers are excessive and overlap in capabilities, the ultimate approach requires a delicate balancing act between cost savings and job protection. This challenge isn’t new; experts have recognized that NASA’s operational network is overextended and many facilities are underutilized. The need for reform has never been more pressing due to the aging infrastructure that significantly hampers the agency’s ability to fulfill its core missions.

NASA’s physical footprint is vast, with over 5,000 buildings estimated to be worth $53 billion, spread across 134,000 acres in every state. A staggering percentage of this infrastructure dates back to the Apollo program era, contributing to a maintenance backlog that exceeds $3.3 billion. Aging facilities limit NASA’s capacity to attract top talent and effectively conduct research and development, as highlighted in a study by the U.S. National Academies of Sciences. The operational independence historically afforded to NASA’s centers has resulted in duplication of resources, including numerous underused wind tunnels and thermal vacuum chambers. While some centers like the Glenn Research Center, Ames Research Center, and Stennis Space Center appear to be prime candidates for closure or consolidation, political pressures from Congress add layers of complexity to any attempts to streamline operations.

Despite the apparent need for restructuring, efforts in the past three decades to reduce NASA’s physical footprint have been thwarted by a Congress unwilling to entertain the idea of job losses in their areas. NASA’s leadership has struggled to navigate the political landscape since significant downsizing means losing support from influential congressional members. Previous internal studies have proposed closing several centers or consolidating operations, yet no real changes have materialized. Instead, NASA managed only minor divestitures of properties with excess capacity. The agency states it is following a strategic roadmap for future divestments, but these efforts seem insufficient compared to the increasing maintenance challenges it faces.

One suggested approach to facilitate necessary closures or consolidations is the establishment of a bipartisan committee, akin to the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) commissions that managed military base closures in earlier decades. Such a committee could help insulate decisions from immediate political backlash, making it easier to recommend practical reforms for NASA based on national necessity rather than local job preservation. However, experts note that NASA’s smaller scale compared to military investments complicates this strategy since fewer options exist for negotiation and compromise. Implementing such structural reforms within the agency and managing political opposition will require firm commitment from top administration officials and may also stretch over several years.

In the short term, the Trump administration is expected to explore cost-cutting measures to meet broader budgetary reductions across the government. Plans could include shifting more responsibilities to private sector partners, which would align well with Trump’s pro-business agenda. A key area for potential savings could be scaling back operational costs related to the Space Launch System (SLS), a government-owned rocket program. Transitioning to commercial alternatives, such as SpaceX’s Starship, could yield considerable savings but would not come without political friction, as local job losses related to SLS operations could provoke strong reactions from Congressional representatives. The political landscape further complicates matters, as many NASA facilities are located in traditionally Republican states, leading to a conflict of interest between cutting operational costs and sustaining local employment.

The interplay of politics, fiscal responsibility, and the inherent need for NASA to adapt its infrastructure poses a critical challenge as the agency stands at the crossroads of potentially significant reform. While serving an essential role in the nation’s scientific and exploratory goals, the pressing need for modernization and maintenance reform in a landscape increasingly dominated by private space initiatives cannot be ignored. The potential for consolidation, while necessary for long-term sustainability, must navigate the complicated web of political dynamics that have thus far preserved jobs over efficiency. As NASA moves forward, whether through the establishment of a new strategic framework or by harnessing private sector capabilities, its path will likely dictate the future of not just space exploration but also its role within the broader federal landscape.