The epic evolutionary journey of cetaceans, encompassing whales, dolphins, and porpoises, stands as a testament to life’s remarkable adaptability. Their transition from land-dwelling mammals back to the ocean represents a dramatic shift, a reverse migration that has captivated scientists for decades. The puzzle of whale ancestry, once shrouded in mystery, has gradually yielded its secrets, revealing a captivating tale of adaptation and transformation that spans millions of years. Contrary to initial assumptions, whales are not closely related to other marine creatures like fish or sharks. Instead, their closest relatives reside on land, including the hippopotamus, deer, pigs, and even giraffes. This kinship places them within the order Artiodactyla, a group largely comprised of hoofed mammals, or ungulates. This classification, far from obvious, was only solidified in the 1990s through rigorous research in molecular biology and evolutionary studies, finally resolving a long-standing debate within the scientific community.

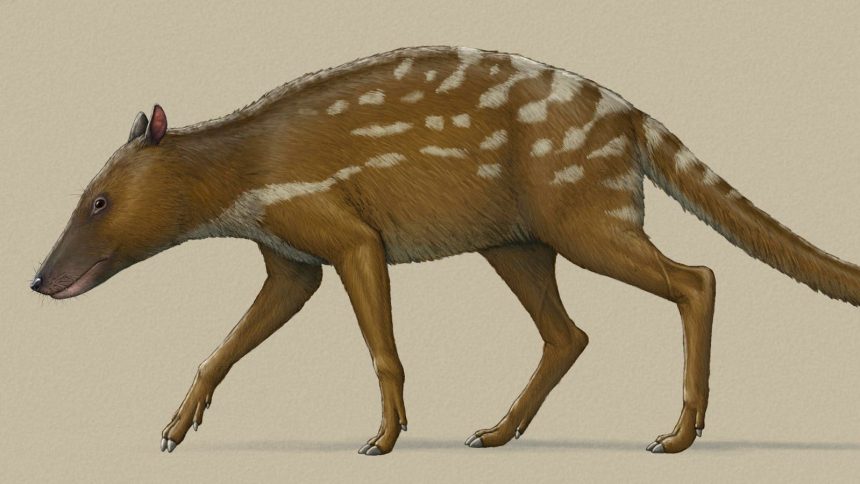

The story of whale evolution takes an intriguing turn with the discovery of a small, unassuming fossil in the Himalayas, far removed from any ocean. This fossil, belonging to Indohyus indirae, a creature no larger than a domestic cat, would prove pivotal in unveiling the terrestrial ancestry of whales. Unearthed in 1971 by Indian geologist A. Ranga Rao, the initial significance of these fossilized teeth and jaw fragments went unrecognized for years. It was only after Rao’s widow donated the collection to paleontologist Dr. Hans Thewissen that the true value of these remnants emerged. Thewissen’s subsequent research revealed Indohyus to be a roughly 48-million-year-old artiodactyl from the Eocene epoch, resembling a small deer-like creature with a long snout, tail, and hooves. The breakthrough came in 2007 when a study published in Nature highlighted a unique feature of Indohyus: a thick ear bone called the involucrum, previously only observed in whales and other cetaceans. This bone, crucial for underwater hearing, provided compelling evidence of Indohyus‘s semi-aquatic lifestyle, bridging the gap between land mammals and their ocean-dwelling descendants.

The involucrum, combined with other skeletal features like dense leg bones similar to those of hippos, pointed towards a creature comfortable in both terrestrial and aquatic environments. Like hippos, Indohyus likely used its heavy legs for stability in water rather than swimming. Further examination of the ankle bone, the astragalus, confirmed Indohyus‘s placement within the artiodactyl order and cemented its position as a close relative of whales. While Indohyus offered crucial insights, the dramatic size difference between this small creature and the massive blue whale, some 15,000 times heavier, underscores the magnitude of evolutionary changes that transpired over millions of years.

Concurrent with Indohyus, another crucial player emerged in the cetacean evolutionary saga: Ambulocetus natans, the "walking whale." This amphibious creature, known from a single incomplete fossil discovered in Pakistan, represents a more advanced stage in the transition to aquatic life. Approximately 10 feet long, Ambulocetus possessed a crocodile-like body, snout, and eyes, suggesting a similar hunting strategy of lurking near the water’s surface to ambush prey. Its ears, however, shared characteristics with both Indohyus and modern cetaceans, further solidifying the evolutionary link. Both Indohyus and Ambulocetus symbolize the powerful draw of the sea, possibly driven by abundant food sources, reduced competition, or greater opportunities for exploration. Their adaptations reflect a dietary shift from terrestrial to aquatic prey, marking a pivotal point in the return to the ocean.

Over millennia, fully aquatic cetaceans like Basilosaurus, and eventually the whales and dolphins we know today, evolved and flourished, leaving behind their terrestrial past. Their adaptation to the marine biome was complete, a testament to the power of natural selection. The fascinating journey of whales back to the sea highlights the dynamic nature of evolution, showcasing how life continuously adapts to its environment in surprising and often unexpected ways. The story of cetacean evolution serves as a reminder of the interconnectedness of life on Earth and the remarkable transformations that can occur over vast stretches of time.

This narrative of whale evolution underscores the importance of fossil discoveries in reconstructing the history of life. From the unassuming Indohyus fossil found in the Himalayas to the more complete remains of Ambulocetus in Pakistan, these paleontological treasures have provided crucial pieces of the puzzle. The meticulous work of scientists, painstakingly analyzing skeletal features and genetic data, has allowed us to trace the remarkable journey of whales from land to sea, revealing a story of adaptation, diversification, and the enduring power of evolution. The ongoing research into whale ancestry continues to refine our understanding of this captivating evolutionary tale, reminding us that the history of life on Earth is a complex and ever-unfolding narrative.