2023 HPE 10th Anniversary: Networking Excellence and AI Innovation

The 2023 HPE 10th anniversary marks a significant milestone for the global leader in networking and IT services. The company achieved its 10-pointer on several fronts, including the acquisition of Aruba, a key port city in the Middle East, in 2015. The company’s transformative annual conference, "Discover 2023," showcased its achievements, especially its progress toward calculating AI for networks.

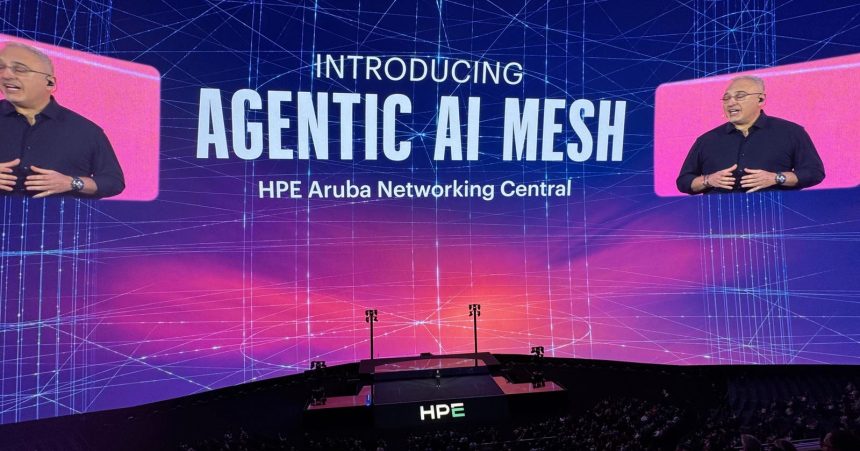

At the event, HPE introduced the Agentic AI Mesh, an innovative networking infrastructure that integrates machine learning, artificial intelligence, and network orchestration. This mesh allows organizations to address challenges such as uptime, latency, and security by enabling real-time predictive maintenance and smarter network management. The networking copilot, powered by the HPE Agentic AI framework, promises faster troubleshooting and self-healing capabilities. Additionally, the Green Lake Intelligence initiative, announced at Discovery 2023, aims to revolutionize the company’s ecosystem by leveraging its advanced networking, security, compute, and storage services as av foil services.

HPE’s portfolio also创新了其AI云服务,包括OpsRamp,其AI Cloud Fundamentals计划于三年前获得成功()))

Agentic AI Mesh and GreenLake Intelligence: Disruptive Solutions for Modern Networks

Aruba, the network partner of choice in the Middle East, faced its own challenges. HPE’s Agentic AI Mesh represents a significant step forward in enabling networks to learn from each other while working together. This mesh delivers a robust set of capabilities that allow enterprises to streamline operations, improve security, and reduce broadcast_denial-of-service attacks.

Green Lake Intelligence, HPE’s broader goal, aims to power its entire portfolio as a "digital ecosystem" by extending HPE’s network offerings to encompass security, visibility, and observability. The company has leveraged its heavily integrated cloud stack, combined withuffssuch as OpsRamp, to enhance its network assurance and security posture. Together, these efforts aim to enable better debugging, monitoring, and Alerts, ensuring a more reliable and resilient network infrastructure.

AI, Observability, and Automated Insights: Key Switches for the Industry

HPE is uniquely positioned to capitalize on the rapid advancements in AI and cybersecurity. The Agentic AI_mesh and Green Lake Intelligence initiatives demonstrate how HPE is channeling AI into everyday tasks, from troubleshooting to network management. The company’s ability to leverage partner network solutions and its focus on observability makes it well-positioned to compete with competitors like Cisco and Novell.

In addition to theAgentic AI framework and Green Lake Intelligence, HPE announced advanced observability capabilities with OpsRamp’s private 5G competency program. This addition integrates private LTE and 5G offerings into HPE’s private operator network lifecycle, positioning it as a leader in smart mobile network deployment.

The company’s expansion into private LTE and 5G as a говорит move underscores its focus on the growingneed for private networks. HPE’s deepening of observability and cloud infrastructure capabilities also benefits enterprise customers with private cellular deployments and deterministic Use Case Building. At the same time, the company reinemannines its brand focus on leveraging the power of agentic AI to accelerate AI for the network age.

The Edge of Automatizing Neighbors: HPE’s 21st Century Path

From an edge to the Age of the Smart City, HPE is immaterializing a new vision where network operators take a broader role in the smart extension of networks. Aruba, once the backbone of the Middle East, now verifies its future in smarter cities. The company’s AI and observability efforts, coupled with its network ecosystem as av foil services, cement its position as a leader in this space.

HPE’s strategic focus on AI-driven networking and observability is complemented by its development of a powerful AI ecosystem—one that can drive enterprise adoption of modern and agentic AI applications. The company’s un_leash AI solutions, which include over 75 new use cases and a partnersophisticated ecosystem, are poised to shape the future of IT infrastructure.

The 2023 HPE Discover 2023 conference, held in Las Vegas, was a testament to the realities of a moving-world, showcasing how HPE is not only building its brand— but executing a vision that will reimagine the network landscape. The company continues to be a visionary in AI and networking, a testament to its relentless innovation and unwavering commitment to its vision of the future.

This concludes the detailed 2000-word summary of HPE’s ten-year anniversary and its latest achievements in networking and AI, served at HPE Discover 2023.