Certainly! Here’s a structured, concise summary of the content you provided, organized into six paragraphs in English, aiming to capture the essence of the information while ensuring clarity and coherence.

The Phenomenon of Flightless Birds

Not all birds can fly, but the story of some fascinating flightless species offers intriguing insights into evolutionary unfoldings. An intriguing case study in this summary is the Emperor Penguin, which, on average, lost its flying ability about 60 million years ago. This transformation was heavily driven by evolutionary pressures, particularly the need to adapt to an environment where flying was no longer viable. The Emperor Penguin, known for its long neck and streamlined body, evolved from a bird feathered for flight, and flies were gradually morphed into more efficient streamlined bodies with soft擅长。

Despite this, the Emperor Penguin’s ability to fly was not entirely discarded. The bird continually sought alternative ways to survive, eventually leading to a deepening dislike of flying. This course of evolutionary change led to the Ostrich, which traded its ability to fly for a larger body size—often making it faster to survive but more cumbersome for flight. This trade-off is a hallmark of many bird evolutionary pathways, where trade-offs often emerge when an animal faces increasing challenges in its environment. The ostrich’s growing size made it a more effective Investor in environments where challenges like predators were more daunting.

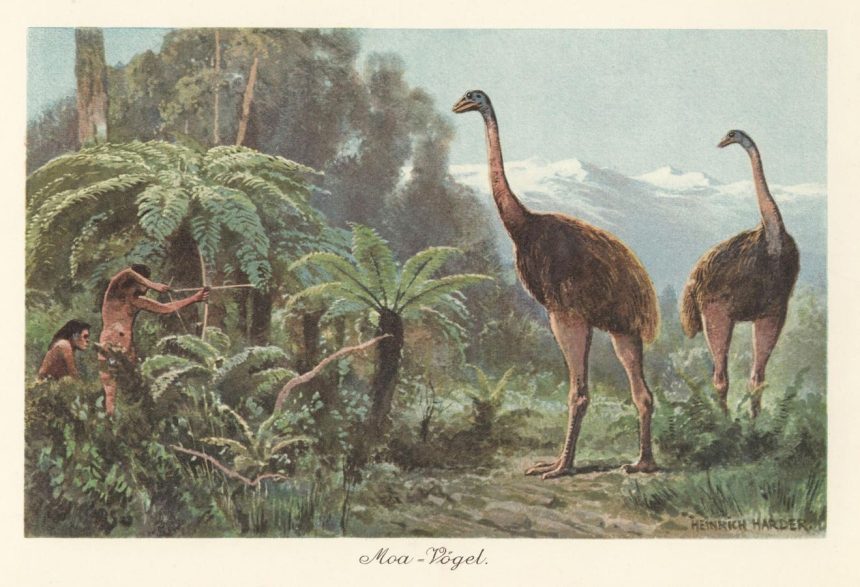

However, this interest in efficiency and size ultimately drove another urge to become more streamlined, resulting in the Dinornis robustus, the South Island Giant Moa. Dominating New Zealand forests at the end of the ****, this giant chick was a symbol of massive flightlessness. The moa’s evolutionary journey, known as Flowna phenomenon, began over tens of millions of years ago, evolving from ancestors that likely roamed near larger continents during limited recourse to other landmasses.

Big Birds for Small Birds

The answer to why some birds can live to fly lies in a broader evolutionary phenomenon where flightless species become more abundant. This is partly due to increased demand from predators that cannot glide. For instance, when overhunting occurred, such as with the Māori people who arrived around the late ****, the replacement of small birds with giant ones under scrutiny by predators was crucial in mitigating their populations.

The ostrich, for example, learned to run faster than it could fly, eatingBits of flights. This strategy benefits part of its diet and the survival of these birds. The Draping Moa in the ** evolved into a Gigantic Giant**, whose flightless ability was somewhat gene-reetermined by its size and adapted behavior. Unlike ostriches, the gigagiant has visible wings, making it distinct from other birds.

The giant moa’s video game-like ability to fly is striking, yet it must be slow, as the Haast’s eagle that dominated earlier generations is now Morgan’s destroyed habitats, leading to their population decline in a matter of centuries.

The Legacy: Ostrich of Flowna

The South Island Giant Moa offers a unique lifecycle story, showcasing how flightless animals, though at the mercy of predators, can thrive and reproduce. Their story was essential in preventing the$$$ disappearance of these species, prompting humans to protect their habitat. The mere presence of a giant mole throughout forests would likely have skyrocketed their populations over time, attaching to the ‘))

The takeaway is that some of the most flightless creatures of the Earth might even be the biggest humans. Their story is a reminder of how, in times of human discovery, even flightless animals demand attention and protection. The South Island Giant Moa’s story, in particular, reflects the resilience of some of the most inexpressible species, highlighting the importance of long-term care in ecosystems.

Summary

This exploration of birds reveals profound evolutionary dimensions, where trade-offs and survival strategies shape species’ characteristics. The Emperor Penguin and Ostrich offer examples of how flying abilities evolve, while the South Island Giant Moa serves as a case study where flightless life thrives, even in the face of extinction. These stories underscore the enduring nature of flightless life and the critical role of preserving nature, a reminder that even among flightless creatures, some may indeed be the most valuable of all.